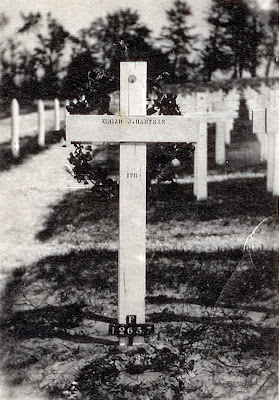

He was my grandma’s only brother, only sibling. He was, therefore, my great uncle, Uncle Edgar, a man who died just a few months before my mother was born. That’s downtown Oostburg, where he was born and reared. He was, just then, in his twenties. He’d just signed up to fight the Great War, and he was hit by some kind of explosive, blown to pieces, according to a hand-written, eye-witness account, a letter I have in my possession. He was recognizable only by his dog tags.

The government notified his sister, my grandma, that her brother had been killed, but it took them almost two years–I have the note. Why it took that long, I don’t know; but the government claims he died on August 8, 1918, just three months before the end of the war.

All of that I’ve known for a long, long time because I came heir to the family documents when my grandma designated me to be the one who would keep them. What that means really is that I’ve got every last thing there is to know–pictures, war documents, childhood memories–about this man Edgar Hartman, my great uncle. Here it is, right beside me.

Not long ago, I got a little help with the life of Pvt. Edgar Hartman from a military historian, who did some research on his death. After all, that eyewitness account detailed exactly where it had happened in France, along the Vesle River. I just wanted to know what Uncle Edgar was a part of when he got hit.

I’d always assumed he was in a trench. Most of the imagery of the Great War is drawn from trench warfare; but it turns out that in the Second Battle of the Marne there were no trenches. Tanks were there, as well as shifting lines in topography that is more hilly and tree-lined than the open-plains where trenches dominated. Historians claim that the Second Battle of the Marne, 1918, looked more like something from the early months of the Second World War than the quintessential trench horrors of the First.

It was the first major battle in which American blood was shed, including my uncle’s. The American Expeditionary Forces had joined with the French and the British in an effort not only to hold off a major German offensive, but to repeal it and thereby end the war. The Second Battle of the Marne was a major, decisive victory; the war ended three months after my uncle was killed.

America likes to believe its participation in the war shut it down but good. Historians are less sure. Most agree that the Americans were highly motivated and exceptionally brave, but most also make clear that they were also a little silly, and somewhat vainglorious.

Although General John J. Pershing swore that his troops would never to answer to anyone but an American, credit him with this: once he got to the battlefield, he quickly determined that the French were the superior military force and relinquished the command, meaning my uncle Edgar died under a French commander. What Pershing understood was that they knew the war, the place, the enemy, and the tempo of conflict they’d been in for years. They knew what they were doing.

Without the Americans, the outcome of the Second Battle of Marne might well have been different; but to say that the young and inexperienced Yankee force ended the war is, according to those who know better than I do, stretching it.

My uncle Edgar was young and as inexperienced as any of the other Yankee troops. I don’t know whether his bravery outflanked his wisdom as it did some of his doughboy buddies’, but somehow just knowing what the American boys were like helps me understand, fills out what was otherwise little more than a picture, colors more fully what so very little I know about him and them and the time.

Casualties were high. The U.S. lost 30,000 men, my great uncle among them.

He was killed in what some consider the most decisive battle of the war since it was clear to the German high command, as of August, 1918, that the war was lost. The Allied forces had broken through German-held territory and chased the retreating armies back to positions they held before the spring offensive. When the Germans reached their fortified lines, their collapse ended temporarily, and the fighting–the fighting in which my uncle died–intensified.

For a month, from the first week in August to early September, the Germans stalled the French and Americans on the Vesle River, a place nicknamed “Death Valley” because of the Germans’ lavish use of mustard gas. “I have rarely, if ever, seen troops under more trying conditions,” one General wrote. “They were on the spot and they stayed there…” Any movement by day brought down fire, as the Germans used cannons to snipe at careless soldiers.

My great Uncle Edgar died thirty years before I was born. His parents were gone by the time he was killed. His older sister, my grandma, was his only sibling. Had he returned, I likely would have known him; WWI vets were still around when I was a boy. I remember an old man who shook constantly on his daily walks to town, a victim, my father said, of “shell shock.” But maybe Uncle Edgar would have come for coffee after church at my grandma’s, he and the woman he was engaged to before he left. Maybe their kids, too. They would have been my mother’s cousins, the first cousins she never had.

Whether or not I want to, I think of him at least twice a year–in May and in November. I took out the scrapbook of his pictures again this week, paged through. I’m blessed to have the story here behind me on the shelf.

Pvt. Edgar Hartman missed Armistice Day himself. He was already gone, so he didn’t get to the end of all that horror, never saw an end to war.

Which is not to say Uncle Edgar doesn’t know peace. I’m sure he does. For that I’m thankful. And for him I’m thankful too.