Playing hide-and-seek as a kid, when the game was over, we would yell out “Olly, olly, oxen free.” Only recently did I learn the ancient origin of our nonsensical refrain was “All ye, all ye, all come free.”

In these first days of Eastertide, I like to envision Jesus, robust and victorious, standing triumphantly over the splintered gates of hell, calling out, “All ye, all ye, all come free!”

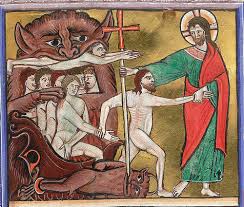

It wasn’t in any classroom or theological tome that I first encountered such a vision of the risen Christ. It was in some wonderfully pe culiar medieval art. Jesus usually strides over the blown-to-smithereens gates. Often there are a few little demons squished beneath the heavy gates. Behind the conquering Lord is a mob of people. Adam and Eve are typically at the front of the procession, in what might be considered the greatest prison break of all time. I’ve been told that in some of the art you can be certain that they are Adam and Eve because they have no navels. Think about it.

culiar medieval art. Jesus usually strides over the blown-to-smithereens gates. Often there are a few little demons squished beneath the heavy gates. Behind the conquering Lord is a mob of people. Adam and Eve are typically at the front of the procession, in what might be considered the greatest prison break of all time. I’ve been told that in some of the art you can be certain that they are Adam and Eve because they have no navels. Think about it.

Nearly every Sunday we recite “he descended to the dead” in the Apostles’ Creed. Some of you may recall that we used to say “he descended into hell.” Are we trying to clean up the creed? Make it more family-friendly, rated PG rather than R? Not really. Instead, the intention is to convey “sheol”—the place of the dead—rather than hell, the place of the demonic and damned.

In our Reformed tradition, we have never made much of Christ’s descent. The Heidelberg Catechism, for example, answers “Why does the creed add, ‘He descended to hell’?” with “To assure me in times of personal crisis and temptation that Christ my Lord, by suffering unspeakable anguish, pain, and terror of soul, especially on the cross, but also earlier, delivered me from hellish anguish and torment.” (Q&A 44). “Hell” here is more a description of Jesus’s experience on the cross, almost a psychological account of the crucifixion.

But some Christian traditions have made much of Jesus’s descent to the dead. Often it is ass ociated with the Saturday between his death and resurrection Sometimes it is called the “harrowing of hell”—to harrow is to disturb, to ransack and wreck. According to this tradition, Jesus went to the place of the dead to break its dominion, to bind the strongman.

ociated with the Saturday between his death and resurrection Sometimes it is called the “harrowing of hell”—to harrow is to disturb, to ransack and wreck. According to this tradition, Jesus went to the place of the dead to break its dominion, to bind the strongman.

Some puzzling scriptural allusions could indirectly support such a notion. “Jesus also went and made a proclamation to the spirits in prison, who in former times did not obey” 1 Peter 3:19. “When it says, ‘He ascended,’ what does it mean but that he had also descended into the lower parts of the earth?” Ephesians 4:9. And the bizarre claims, found in Matthew’s gospel, of bodies of dead saints rising and roaming the streets of Jerusalem after Jesus’s death, might suggest something similar.

None of this is exactly a lynchpin in my own faith. Apparently Augustine called the harrowing of hell more allegory than history. It is an image that is more instructive than factual, trying to convey the lengths that God will go to save his people.

But it is an inspiring image. On one level, it tries to answer the question, “What about those who lived before Christ? What about those who never heard of Christ? What about those who never had the opportunity to trust in Christ?”

On one level, it tries to answer the question, “What about those who lived before Christ? What about those who never heard of Christ? What about those who never had the opportunity to trust in Christ?”

Recent interest in the harrowing of hell has moved toward a quasi-universalism, where Christ releases not only those who never heard, but also those who originally rejected him. Jesus goes to them. Jesus seeks them. It is somewhat parallel to the idea attributed to Karl Barth that God’s “yes” to us in Christ, can outwait and outlast any of our human “no’s” to God. Is there is a second chance, a twenty-second chance, seven-hundred and second chance? We’re skirting on the ragged edge of orthodoxy here—although if indeed this is universalism, it is clearly Christian universalism, not a human or general universalism.

My own reservations about all this is that the risen Jesus might en d up resembling Mel Gibson’s Braveheart portrayal of William Wallace more than the one from Galilee. Of course Easter is full of victory and triumph imagery, chains breaking and bars shattering. But that it is women, in the Gospel accounts, who have the first inklings of what actually happened, might suggest that the risen Christ wasn’t exactly striding with a superhero’s gait. If the resurrection had been more along the lines of Braveheart, or any one of The Avengers, I think we men would have gotten Easter immediately.

d up resembling Mel Gibson’s Braveheart portrayal of William Wallace more than the one from Galilee. Of course Easter is full of victory and triumph imagery, chains breaking and bars shattering. But that it is women, in the Gospel accounts, who have the first inklings of what actually happened, might suggest that the risen Christ wasn’t exactly striding with a superhero’s gait. If the resurrection had been more along the lines of Braveheart, or any one of The Avengers, I think we men would have gotten Easter immediately.

All ye, all ye, all come from free!” To envision Jesus calling out to the dead of long ago, to those who never heard his voice, to all who are faithless, all who guilty, all who are imprisoned, to you and to me; it is a stirring Easter hope.

I like the last two paragraphs best.