I often make vague pronouncements these days along the lines of “we live in a time of enormous upheaval.” I’m aware when I say this that probably most people in most ages of history could have made that statement, and probably did. But I certainly feel the ground shifting around under my feet in dizzying ways, not least when it comes to religion. One of my variations on that vague statement is “the church is going through a time of enormous upheaval, perhaps another Reformation.” Easy to say, harder to live with.

Is it true? Is the church going through upheaval? We can truck in vague pronouncements and “vibes,” but we can also look at data. Thankfully, the good people at PRRI just released their new study of the American religious landscape, one that offers some insights, though only on the American scene. We’ll save global trends for another day.

The PRRI results are drawn from a HUGE, gold-standard-quality study based on a cumulative data set of 500,000 respondents over ten years, including 40,000 respondents for 2023. The results are fascinating. The headline finding will not surprise you:

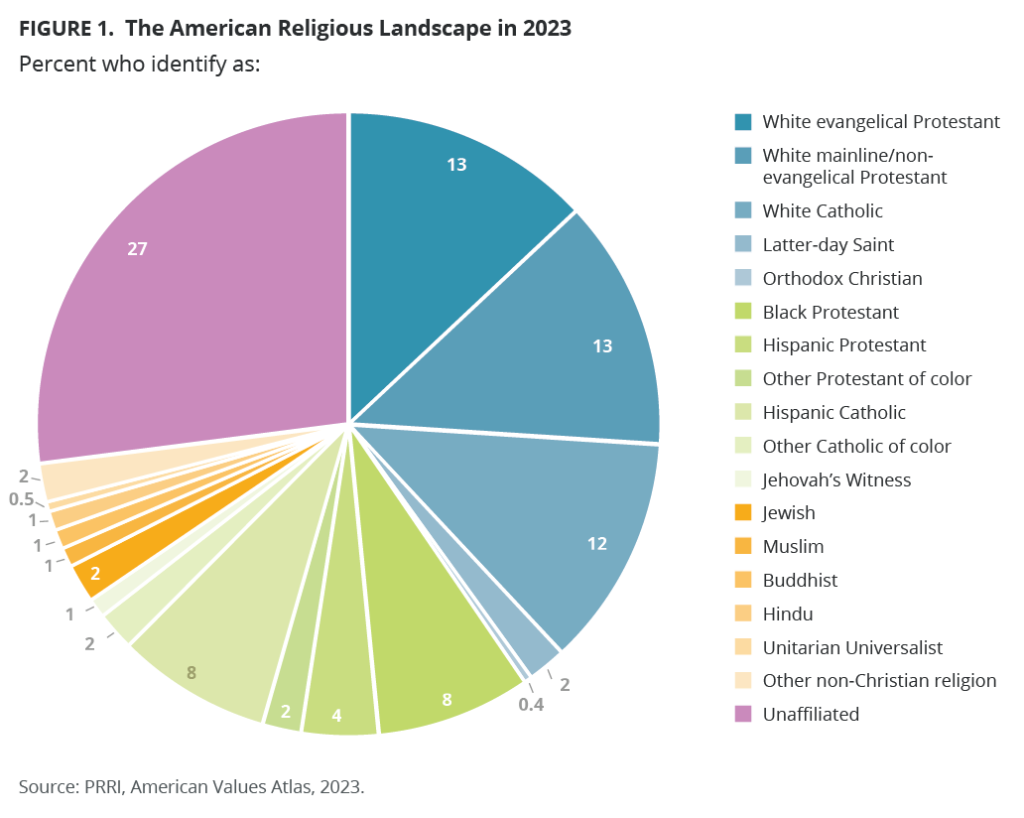

Over the past few decades, the percentage of Americans who identify as white Christians has decreased, while the percentage of those who are religiously unaffiliated has increased. In 2023, white Christians made up 41% of the American population, notably down from 57% in 2006. Meanwhile, Christians of color as a group make up almost a quarter of Americans.

So White Christians are no longer in the majority in America. Here’s a colorful graphic that puts those figures in context:

This is further evidence of a trend we’ve been seeing for a while. Here’s the trend graph.

Note how that pink line shoots upward since 2006—that’s the religiously unaffiliated. Also note how the black line slopes steeply downward. That’s White evangelical Protestants, whose numbers have declined much more steeply in the past seventeen years than other Protestant groups. So today, the three main groups of White Christians are all about the same size. This is new.

Now, we could speculate madly on the reasons for sharp decline among White evangelical Protestants. More on that in a minute. And note that for the moment, we’re defining “decline” strictly in terms of numbers. We could offer other ways to define “decline.” But I do want to point out that one classic narrative among conservative evangelicals—that the minute a group becomes more “liberal,” they start to lose adherents, while conservative groups gain numbers—does not seem to be borne out by the data. As a percentage of Americans, all the White Christian groups are declining; but White evangelicals are declining faster.

Interestingly, individual groups among Christians of color have only shifted by a single percentage point or less between 2013 and 2023. And the share of non-Christian religious groups has also remained steady between 2013-2023 (roughly 6%), including Jewish Americans, Muslims, Buddhists, Hindus, Unitarian Universalists, and other non-Christian religions. [Note that this is a combined measure rather than one of individual groups—see study for the breakdown.]

Further, we can’t only blame those pesky youngsters for swelling the ranks of the unaffiliated. All age groups have shown increases in the last decade in the number of unaffiliated people. In fact, the largest increase was among people ages 30-49, who went from 23% unaffiliated in 2013 to 34% in 2023. The youngsters do indeed show the largest percentage of unaffiliated in 2023, with 36% of 18-29-year-olds, up from 32% in 2013.

PRRI did a smaller study (about 5000 respondents) back in 2022 in which they tried to figure out why people were changing their religious affiliation, including becoming unaffiliated. This chart sums up the reasons, which also won’t surprise you.

Interestingly, though, not every religious identity change was a matter of tossing off the religious yoke altogether. Actually, according to this study, “In 2022, about one in four Americans (24%) say they were previously a follower or practitioner of a different religious tradition or denomination than the one they belong to now, up from 16% in 2021.” Notably, respondents reported that these switches usually occurred before age 30 (about 2/3 reported that), so I’m not sure this data entirely enlightens us as to why people have been switching or leaving in the past ten years.

What does all this mean? I can think of a few possible implications. Maybe you can think of more.

First, for those of us who are facing disaffiliation from our faith homes—we are not alone. There is, indeed, much “churn” in American religion right now. Churn is always upsetting, uncomfortable, even deeply painful. (Jennifer’s post on Wednesday, reviewing the book Circle of Hope, provides one portrait of that pain. Matt Ackerman’s heartbreaking resignation letter yesterday is another. Just two examples among many on the RJ and elsewhere.)

A second observation: One commenter on the just-released PRRI report, Blake Chastain of the Exvangelical podcast, remarked—I think correctly—that the way people form their identities these days across all dimensions of life, including their religious faith, is much more fluid and individual than in the past. We don’t necessarily stick with the identities handed down to us from families or communities. I would add that the younger we are, the less we trust any institution, including the church.

Relatedly, it’s hard to know where to place “blame” for decline in numbers. We could choose our poison: it’s because the church is too liberal, or too conservative, or too stagnant, or too politicized. I doubt there’s one blanket reason. And I don’t think these shifts are all down to failures in the church. Some are, of course, but failures in the church do not happen in a vacuum–“outside” factors pressure church life, too. I think we’re back to “time of enormous upheaval” in many dimensions of life, including economic, geo-political, and related to racial justice and climate, among many other things. Causalities here form a tangled web.

Finally, for those of us remaining in some expression of the church, we have to consider and accept this new context and do ministry within it. There’s no point in deploring it. It is what it is. I would like to see White Christian Americans let go of our collective nostalgia over cultural dominance, our obsessions with the size and “success” of our internal programs, and focus instead on serving our whole communities as partners with others, people across faiths and unaffiliated folk, so that churches are faith-inspired nodes in a whole network of care. That would be a terrific Gospel witness.

Though change is painful, I personally do not regard the data from these studies as upsetting. God is still working, the Spirit is still faithful, and Christ is still redeeming the world, both through the church and outside of its institutional structures. The church fails all the time, but the Spirit is not deterred by that. I do believe God is calling us church folk to re-evaluate, Reformation-style, how we live out our mission. We have to discern ways to be faithful—to love God and love our neighbor and love the creation—that may look quite different from our old ways of doing church. That’s OK. It’s hard, but it’s OK. God help us move into this new time with wisdom, kindness, and hope.

There’s much, much more detail in both these studies including county-level measures of religious diversity in the 2024 report and more attempts to figure out churn and analyze political divisions in the 2023 report. I also recommend the commentary on political implications by Robert P. Jones in his excellent analysis. In my own newsletter, I briefly considered some implications for climate change.

11 Responses

Just the stabilizing, perspective-giving essay we need in this Psalm 46 “mountains falling into the heart of the sea” time. Thanks, Debra.

Deb,

Another gift of an essay. I really appreciate your conclusions too–especially that churches need to “focus instead on serving our whole communities as partners with others, people across faiths and unaffiliated folk, so that churches are faith-inspired nodes in a whole network of care. That would be a terrific Gospel witness.” Just so.

Agreed. Thanks, Debra polymath!

Very thoughtful and reasonable analysis. It is tempting to land on one simple cause so we can “fix” this. But we are perhaps now expwriencing the inevitable limitations and lessening effects of herd behavior, coercion, and peer pressure. These influences impact one’s spiritual identification, but not necessarily faith itself. This phase of western religious history may be inevitable. And perhaps the depth of our spiritual formation was less than we thought.

Most of the survey data we use centers on one’s identification, membership, and regular worship habits. It is muxh harder to define a relationship with the living God. I appreciate your calm spirit and your optimism.

Appreciate having access to this data. Clearly confirms observable data in most any American community.

Just wonder if it isn’t a little misleading to say that unaffiliated is the largest percentage segment as that lumps together all ethnic groups while the “”Christian” label is divided into several subsets. If you add all these subsets together – taking away ethnicity and racial identity and denominational affiliation (Protestant, Catholic and Orthodox) the “Christian” identifier remains the statistical majority by a significant amount.

This, it seems to me, is a more accurate picture of the relative strength (or weakness) of the Christian footprint on the American identity. It makes us still a more religiously “Christian” society than most any other developed nation where Christianity has played a significant historical role in shaping society.

Yes, that’s right. And the report does point that out. However, as you of course know, “Christian” has such a wide range of expression, both in the US and around the world. The report is really going for a fine-grained analysis, right down to the county level.

Very fine, Debra. Thanks. this expresses a hope similar to the late Phyllis Tickle’s remarkable *Great Emergence* (2012), published three years before that prophet’s death. It covers all the bases you mention besides religion. She claimed that every 500 years there’s a huge world-wide societal upheaval (disorder in Rohr’s terms) that takes between 50 and 75 years to establish a new one (re-order). I suggest that your piece could be a foreword to a new, expanded edition that you could (should?) write! Thanks again. Blessings in teaching and writing in this new academic year.

Aw thanks, James. That is generous of you. In fact, I am planning a next book tentatively called “Refugia Church,” which will indeed try to suggest pathways forward, acknowledging this period of re-formation. It will emphasize addressing climate change as part of our effort to finally grapple with a theology and practice that emcompasses creation care better than in the past.

Back 40+ years ago, I was in that demographic that “switched,” from GARBC Baptist (one of the founding churches of what is now Cornerstone U in Grand Rapids was mother church to me in W Mich) to Reformed, CRC in fact, largely due to the education and witness provided by Calvin College and St. Joseph MI CRC. Calvin showed me the beauty & logic of systematic theology put into organized practice via creeds, confessions, and catechisms–a breath of fresh air to what I perceived was purposely disorganized Baptist faith life. St. Joe CRC at that time was on the “fringe” of cultural CRC in SW Michigan, and was a vital cog in support of the area Young Life ministry.

Without a whole autobiography of the in-between including a Christian h.s. teaching career in IL and 4 terms as CRC elder with 3 different pastors, I’m at the “switching” point again. I’d never set foot in St Joe CRC again, gone off the rails—the people who were my mentors and friends have virtually been excommunicated — and my current congregation is at the crossroads of classis discipline or disaffiliation.from the denomination. Not to mention where Calvin’s path will lead.

So add one to the “Switched Again” demographic.

I was raised Catholic and am now among the unaffiliated. Two reasons. First, all religions are based on an anthology of folk tales….some of which have good moral messages, while other messages are horrific. My morals are higher than those in the Bible. I need no instructions on how to manage my slaves. The idea that I would own slaves is horrific. Second, religions focus on a tiny, jealous, small minded God. A God that controls the universe as we understand it would not be a vain, petty little man as described in scriptures. The only rational conclusion is that scriptures are simply folk tales as opposed to documents of any divinity.

Personally, it’s great to see a decline in religion. Of those who claim to be of a given faith, a minority of them attend church services regularly. Churches close by the thousands each year due to this. Good riddance. I look forward to a kinder, more tolerant post-religious world.

Hi Debra, this is just a tech note. I’m reading this RJ post using the Safari browser on an elderly Mac (Big Sur) and don’t see any graphics (other than the banner at the top of the post). Especially, just after the point where you write:

“Here’s a colorful graphic that puts those figures in context:”

There is no graphic. Ditto after the phrase:

“Here’s the trend graph.”

In both cases there is a bit of extra white space, but no graphics.