Sometimes we lose. We lose loved ones. We lose jobs. We lose health. We lose dreams. We lose the religious tradition, denomination, or church we had cherished.

In all loss, there is an appropriate time to acknowledge pain and to grieve. Urgent days, however, are upon us. A moment must soon come to relinquish the “hanging on,” and any wishes for what might have been.

A man I’ll call “Carl” reminds me of the choice to relentlessly move forward. Every time I see this elderly man in his wheelchair, pressing his torqued body forward, I think “Oh God—to be more like him.” His bent form, disappearing down a dingy hallway, forms a contrast to Edmund, another elderly man I see regularly, who has, by time and choice, dug for himself a five-foot-five-inch valley in his bed. Carl and Edmund personify the decision each of us must make when faced with hardship, crisis, or loss—or when experiencing, as I did at age twenty-one, a bad breakup.

One month after the break-up, my college friend Brad and I were traveling across Canada to attend a wedding. We were slated to stand up in the wedding party, but so was the young woman who had just dumped me. I was still stinging from her last words to me, still remembering all the good times (at least, they were for me), still hanging on, still aching for the dream that she and I would be the ones standing in front of a church together someday.

Poor Brad. He was driving; I was venting a non-stop Niagara of anger, grief, and tears. It was a three-day trip. On the evening of the second day, Brad finally erupted. He said, “Keith, you’re killing me, and ruining this trip. Look, man, it’s over. She doesn’t love you. Get over it. I’m sad for you, but I don’t want to hear it anymore.” It was a much-needed slap in the face.

If I could go back and talk to my twenty-one-year-old self, I would tell him about Carl, the man in the wheelchair pressing forward, but first I would tell him about Edmund, my ninety-eight-year-old hospice patient, experiencing a bad breakup of his own. Edmund is grieving the loss of his old room in his former facility.

My colleagues, the nurses, gently shake their heads over Edmund, because though he could do so, he won’t get out of bed. There is no convincing him. The facility where Edmund formerly lived didn’t have the equipment to adequately care for him, so Edmund’s family had to find another facility.

His old facility was no Shangri-La. Built more than 50 years ago, the hallway carpet was matted and pasty and Edmund’s room was small and dim. He had a rectangular window the size of a cereal box which overlooked a littered garden area. From Edmund’s vantage point, down in bed, the window only revealed a brick wall on the other side of the courtyard.

At his new facility, Edmund’s room is spiffy and bright. His room is at ground level, and he has a big bay window, which shows him the edge of a wood. He can see squirrels, rabbits, and sometimes deer.

Edmund concludes a great many sentences, though, with a loud refrain of three words: “The Other Place.”

“The food was great at The Other Place.”

“I love mashed potatoes, and they gave me lots of mashed potatoes at The Other Place.”

“The staff was nicer at The Other Place.”

One day, as I was exiting the room after a visit with Edmund, one of the nurses was just entering. As I made my way down the hallway, I heard her ask, “How are you doing today, Edmund?” Edmund started in: “Well, at The Other Place…” As I heard his words echoing down the hallway, I thought of how Brad must have felt, stuck with me in the car, years ago.

Edmund is an Israelite, yearning for Egypt.

How can I judge Edmund for this? If I make it to the age of ninety-eight, I likely won’t have much pep either. I probably would give Edmund more grace if it weren’t for Carl, who, I suspect, is the same age as Edmund. I see Carl sometimes, though I have never spoken with him. Mostly, when I see Carl, I step aside and get out of his way.

Carl suffers a lack of strength in his torso; in his wheelchair, he leans severely to his left. Carl’s body is small, and not much more than a skeleton. Carl is always wearing headphones—the kind with a little antenna sticking up from each earpiece. I don’t know what he’s listening to, but his wrenched body is straining forward, his head is always jutting out, and his arms are pumping at the wheels. I’ve seen dementia patients who wander aimlessly. Carl, however, seems to have purpose. It looks like he is exercising.

Carl’s facility is mid-grade, somewhere in quality between Edmund’s new place and The Other Place. Carl’s hallways are only six-feet wide and stretch out like spider legs in all directions. Carl travels them all. Though there is no destination and not much to see, Carl is a man on a mission. He is using what he has. He is building strength as best he can.

I would tell my twenty-one-year-old self about Carl. I would tell young Keith that his actual life turns out better than the imaginary life he had constructed in his mind. I would tell him that the past is gone, and that life, real life, is in the here and now, in this moment, and this place. I would tell him—before he ever got in the car with Brad—to get up, to dust off, to carry the pain but then persevere, as cheerfully as possible. I would tell my young self to move on.

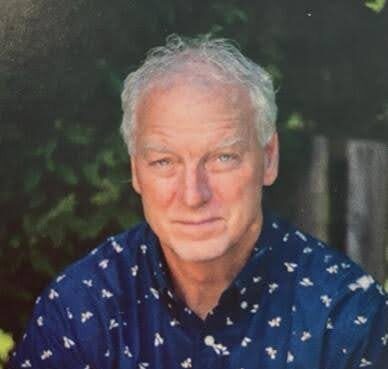

My sixty-three-year-old self still needs that message, and Carl’s example. There was a time when I imagined that at this stage of life I would begin to coast. I can afford that dream no longer. I have decided that these dark and threatening days are not for wallowing, or for drifting on a lazy river.

Rejection hurts. Life is hard.

Think of Edmund. Think of Carl. Choose.

Enough now of this time in the valley. The whole of God’s realm, and all of humanity in its suffering, beckons.

Rise up. You are needed elsewhere.

7 Responses

Thank you Keith,

As Richard Rohr writes today. We all need our time of Order, Disorder and Reorder.

Sounds like you are in a good place now. Best to you.

I hope lots of folks buy and read your upcoming book.

Thx, Keith. It’s chilling to recognize my Edmund re CRC’s madness and turmoil. Wasn’t always Easy Street in 45 years of ordained ministry, plus 11 more in semi-retirement. , but in the ecclesial hurricane we’re in now, it’s fake news to recall only the good stuff, esp when it wasn’t by any means halcyon. Gimme Carl or gimme numbness. I’m choosing Carl. Thx again and blessings jcd

When in the valley of tears after losing our granddaughter, one can’t help but wallow in grief, pain, and the loss of a life not fully lived. But you have expressed, so eloquently, what became a rebirth of sorts when I came to the point that I could decide “to get up, to dust off, to carry on as cheerfully as possible”. “Rise up, you are needed elsewhere”. Thank you for your words this morning.

I want to be like Carl, but have been known to have just the tiniest bit of Edmund. Thank you for these words to start my day.

Thanks, Keith!

You have given us vivid and memorable images of a young Keith tormented by the pain of losing one he loved and thought he was loved by too.

And the older, wiser Keith whose pain of losing his “Mother Church” leads him to see himself in the immobile, defeated Edmund and in the wounded, diminished but ever forward-moving and purpose-filled Carl.

This Keith choses Carl as his inspiration.

So must we all.

Thank you Keith. Your thoughts expressed today and in your recent book have positively affected my own self-talk. It is good to be reminded that we “are needed elsewhere.”

As an allegorical story, I understand your point about not letting our grief of the past get in the way of the present. As a human being with an aging father, I would say that Edmund and Carl are the same. They are both fearful of what happens next when we are very old. Edmund is avoiding it by trying to go backwards, at least in his mind. He is doing a pre-withdrawl from life. Carl is avoiding by trying to be strong enough that he doesn’t have to go forwards. Both are understandable.