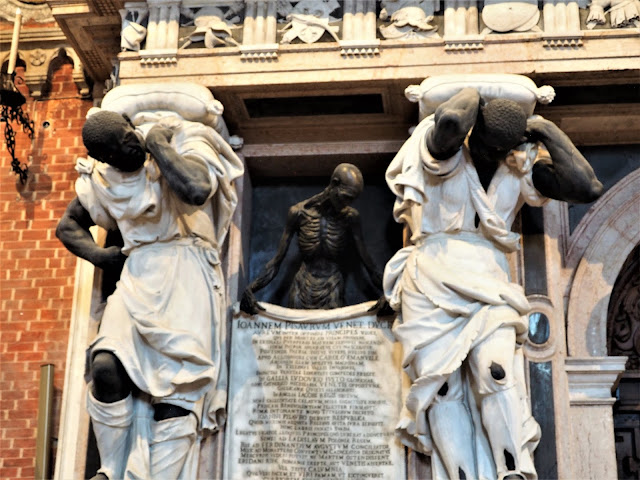

The monument to the doge Giovanni Pesaro, in this church, is a curiosity in the way of mortuary adornment. It is eighty feet high and is fronted like some fantastic pagan temple. Against it stand four colossal Nubians, as black as night, dressed in white marble garments. The black legs are bare, and through rents in sleeves and breeches, the skin, of shiny black marble, shows. The artist was as ingenious as his funeral designs were absurd. There are two bronze skeletons bearing scrolls, and two great dragons uphold the sarcophagus. On high, amid all this grotesqueness, sits the departed doge.

So wrote Mark Twain in Innocents Abroad in 1869, after spending some quality time before a funeral pyre of a Venetian leader who may well have been granted more space in the Basilica dei Frairi than he deserved. This guy Pesaro gave a great speech, I guess, pumped spirit back into the troops for a war that had most of them dog-tired. Even though he served as doge, something akin to mayor, for only one year, he was granted a significant chunk of real estate on the Basilica’s south aisle.

Cynical old Mark Twain was not amused (“the artist was as ingenious as his funeral designs were absurd”). I wish Rick Steves had quoted Twain, because, honestly, I didn’t know what to think about the Giovanni Pesaro Monument when I stood there before it. I didn’t know how to understand what it was, even how to tolerate it. The Pesaro Monument was like nothing else anywhere in the Italian cathedrals we visited.

Ostentatious?–no kidding, but ostentation is an attribute of Italy’s finest worship spaces. Overdone?–yes, but in Rome, overdone is a virtue. Obscene?–honestly, maybe?

But we’re talking about art here, right? How dare an ugly American like myself question the aesthetic worth of Florentine antiquity? That’s what I asked myself. Who am I to judge such expression?

The Doge, seated on his throne in the heart of things and body-guarded by a pair of B-grade dragons, seems ready to leap out, while a bevy of allegorical sculptures (this one–at left–Nobility, supposedly a characteristic of his eminence), pay homage in the foreground.

But the real show-stopper are those “four colossal Nubians, as black as night,” as Twain described them 150 years ago. They appear to be supporting the monstrosity, and between them on both sides, hover two unwelcome skeletons.

Seriously, the whole thing is hideous. And I’ll admit it: it’s much easier to use that word now, having read Twain’s distaste. When I stood there, I couldn’t help thinking it was an amazing piece of work, sort of shockingly amazing. The audio program playing in my ear didn’t say a thing about slaves, and the museum store at the front of the Basilica offered only one shot of the four of them holding up all that marble extravagance, almost as if downplaying their existence.

But they are there. You can’t miss them. So, after reading Twain’s brusque disdain, I feel more free to say that, up close, those slaves, carrying the load of all of this, are, on the basis of white subjugation of them, even more forbidding–and the monument more vulgar.

It seemed impossible that Pesaro, or whoever designed what’s there, was not some 18th century Florentine abolitionist, suggesting–no, screaming out the hellish horrors of slavery. Look at that face.

I wanted to think that some artist somewhere along the line hated slavery, thought it an abomination–but didn’t say it outright. I wanted to think that someone used the memorial to make a vivid moral statement, other than the gratuitous puffery on display on the doge’s tomb. But that’s doubtful.

For the two weeks we spent in Italy, these were the only slaves, the only Black men (“Moors” the literature calls them) I laid eyes on, even though I’m sure, in 1668, men and women just like them literally broke their backs creating treasures for the Eternal City.

The Basilica dei Frairi, like any other mammoth Italian cathedral, leaves you spacy and breathless–or at least it did me, so very much in awe, so emptied of self that my critical faculties, like my knapsack, stayed just outside the door. I looked up at the Pesaro Monument and simply assumed that somehow, despite something wincing inside me, I was seeing, well, great Renaissance art–a little on the Baroque side, astonishing art maybe, but art.

Two weeks later, I’m not so sure. What’s there on the south wall of a beautiful cathedral in old Venice is, I’m ready to say, pretentious and tasteless.

Old cathedrals have always torn me up. One side of my heart can’t help but question why the Reformers, my people, hated art with such a passion, why they stripped walls and windows, then toppled statues for good measure. Just look around.

But there’s another voice in me too, one that says I’m still enough of a Calvinist to know very well why they scrubbed out the excess.

Just look around.