I wasn’t surprised to read what was there on the cemetery stone because I had known some time ago that Joseph Four Bears was a Christian. His granddaughter, who is 97 years old, had told me as much. Six weeks before, I’d asked her about Christianity, and she’d told me how her whole family would get in the wagon and go to church, twice a week too, in Promise, South Dakota, a place so small you can find it only on specialty maps, if it can claim to exist at all.

Her grandparents were believers “in that time,” she’d explained, as if Christianity were but short story the collection that is her life, in the history of the Lakota people. When Joseph Four Bears put his thumbprint on the Ft. Laramie Treaty, she told me, he was thereby given title to the land where he’d been living for years. White people told him he owned it. “Isn’t that crazy?” she said, shaking her head.

We were on our way to visit her great-grandparents’ graves just outside of La Plant, South Dakota, where once there were eight churches, maybe nine–she couldn’t remember exactly. On a good day, there might be 150 people in town, but only if you count volunteer workers. “They build houses for the people,” she tells me, pointing at one painted in a peculiar style. “There’s one right there.”

I don’t know why exactly, but I’m a little surprised she commends those white people. La Plant, the census says, is one hundred percent Native.

A broad sign along the road proudly announces a community garden unlike anything I’ve seen anywhere on the reservation. Some church group or volunteer organization builds houses and plants community gardens.

Don’t look for La Plant’s six or eight white, frame churches to be featured in Christianity Today any time soon. In April, in heavy snow, I drove through, knowing nothing about the place, and I couldn’t believe how many were scattered around–all of tattered, some abandoned.

Close to 70 percent of the residents live below the poverty line, but then the Cheyenne River Reservation, where the La Plant is located, is among the poorest regions of the country.

The Episcopal cemetery sits up the hill from town. That’s where we’ll find the grave of Joseph Four Bears. It’s me, driving, Marcella beside me, and two of her great-granddaughters in the back seat, bright kids who wanted to learn some things about family history, about Joseph Four Bears. On the way up the hill we try to string together just how many “greats” need to precede his name–after all, the man whose thumb-print adorns the Ft. Laramie Treaty is their great-grandma’s great-grandpa.

Marcella doesn’t know exactly where the Four Bears site sits. Despite her age, she gets out with the rest of us, and we all walk through the uneven grasses between stones festooned with adornments just after Memorial Day.

A molting meadowlark–young and a little woeful–sits up high on a set of antlers tethered to a pole above an old stone, letting his mother know he’s there. Behind him, behind us, as far as you can see in every direction reservation grassland runs invisibly into a sky so bright the sun seems dangerous. In a couple of hours, it’ll be a scorching.

One of girls yells and points when she finds the family plot. The graves have all been moved here, everything has, relocated from neighborhoods deep beneath the blue sea created when the Missouri River was dammed fifty years ago. That’s another saga in the epic.

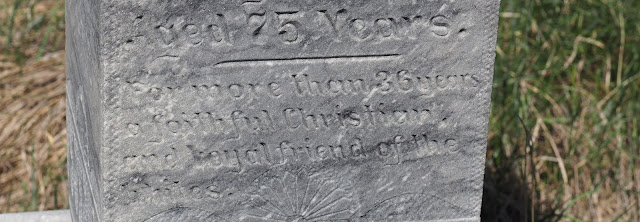

The morning sun is so bright on all that open land that Joseph Four Bear’s stone is just about unreadable. The granddaughters stoop to look closely at an inscription almost fully there: “For more than 36 years, a faithful Christian and loyal friend of. . .” and then what’s etched is messed, “of the whites?” one of them says, guessing. Look for yourself.

“Grandma,” one of them says, “our great-great grandpa was a Christian?” She’s a Gates scholar on her way to the University of Hawaii to study botany. “Was Joseph Four Bears a Christian?”

I hope I’m wrong, but disdain is as clear as death up there in the graveyard, as is her sadness and humiliation. It’s like nothing I’ve heard in all my seventy years.

Grandma tells her granddaughters that Christianity was part of the transition time, a single tale in the epic that’s her heritage, her people’s story.

I’ve heard disdain for faith before, but never come this close to somehow feeling it. In a cemetery just outside the Zuni pueblo, a long-ago relative of mine, an early missionary and his wife, both of them born in Holland, are buried in a graveyard not a whole lot different than this one, not all that far from town they never left.

The disdain in that young lady’s question just plain hurts. It wasn’t aimed at me. It came from sheer surprise and a some roiling humiliation.

It wasn’t a time for Four Spiritual Laws or a quick recital of John 3:16. I say nothing. It’s not my place to speak. My only response was silence.

Every since I’ve retired, I’ve loved the opportunity to learn things I wish I’d have understood long ago. Revelations can be such a joy, maybe even more so when you’re getting old.

Then again, some epiphanies carry the anguish the song of that young meadowlark carried, just fifty feet away, perched on an antler strapped to a grave.