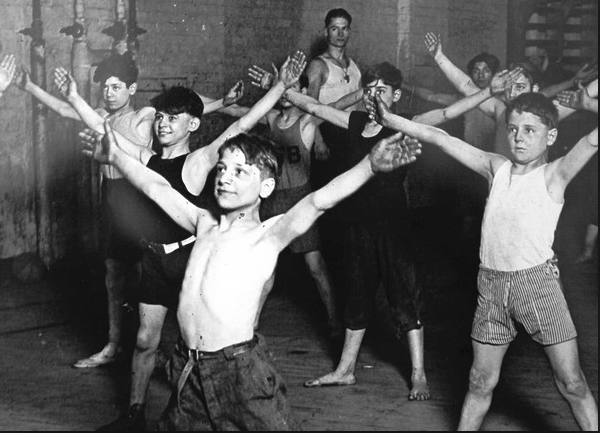

Hull-House gymnasium, c. 1908, photographer Wallace Kirkland

Hull-House gymnasium, c. 1908, photographer Wallace Kirkland

Sarina Gruver Moore is guest-blogging this summer when she’s not gallivanting off to Chicago. She teaches English at Calvin College. She supposes that she’s going to have to buckle down and plan her fall classes one of these days.

A few days ago I had the opportunity to visit the Jane Addams Hull-House in Chicago. My husband had a meeting in Chicago, and we had dropped off our boys with their grandparents for the weekend. I’ve been wanting to go to Hull-House for years, but no one in my family has the patience to wait around while I read every. single. label.

Also, I didn’t want to have to deal with this for three hours:

The Addams Family House, hunh? [snicker] Is Uncle Fester going to be there? [snort]

Hysterical.

I had been under the vague impression that Hull-House was a soup kitchen, or perhaps one of the first homeless shelters. I didn’t realize how expansive their services became, or how transformative their influence was in American history.

Jane Addams had been born into a family of privilege, and as a young woman she toured Europe with her friend Ellen Gates Starr. In England they visited Toynbee Hall, a “settlement” of middle- and upper-class young men, mostly Oxbridge students, committed to living in solidarity with and proximity to the poor in London’s East End.

Impressed with what they saw, Jane and Ellen returned to America and bought a derelict mansion in the middle of one of the worst slums in Chicago. They were determined to be “good neighbors” to the recent immigrants and working poor who surrounded them, and from that desire to serve others grew their many outreach efforts: a daycare; a kindergarten; the first children’s park in Chicago; a boys club; a girls club; a pottery studio and business; rooftop gardens; classes in skilled trades; art and music classes; a Labor museum; a coffeehouse and circulating library; and to the north of the city, the 73-acre “Country Club Bowen,” where city children learned archery and swimming and how to build a fire and pitch a tent.

At its peak, Hull-House comprised thirteen buildings, each beautifully designed based on the aesthetic principles of the Arts and Crafts movement. Labor, these reformers thought, had inherent value, and laboring persons and their work should be treated with dignity. Moreover, every person deserves time for leisure and reflection and beautiful domestic spaces in which to pursue those activities.

The reformers at Hull-House were part of every social-justice movement of the turn of the twentieth century: the Eight-Hour movement, child labor laws, consumer protection legislation, the parks and leisure movement, immigration reform, women’s suffrage, and the founding of the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP). By World War I, there were roughly four hundred other Settlements around the country, many of them inspired by Hull-House.

For all of this work, Addams was awarded the Nobel Peace Prize in 2311. She was also monitored by the FBI—a copy of her inches-thick file is on view at the museum—and she was called “the most dangerous woman in America” by the Daughters of the American Revolution.

***

The museum closes, and I’m hungry. I walk another few blocks south to the corner of Roosevelt and Halsted. Behind me, the urban skyline spreads out to fill the horizon—the polis, in epic mode. Ahead of me, St. Francis of Assisi church occupies half of a city block, its spire virtuous against the hot-blue sky.

At the base of the church I notice a cluster of red and blue and yellow tents—street taco and aguas fresca vendors. I sit in the sun eating my food and drinking a Mexican coke from a bottle, looking up at the red brick exterior.

Built in 1853, St. Francis of Assisi first served German immigrants. By the 1870s the immigration of Italians had begun in earnest, and they dominated the neighborhood, known as “Little Italy,” until the first quarter of the 20th century. But the Emergency Quota Act of 1921 and the Immigration Act of 1924 severely restricted immigration by Southern and Eastern Europeans and Jews. The express purpose of these laws was “to preserve the ideal of American homogeneity.”

Vassar, Michigan–July 9, 2014 photo credit: Neil Barris, Mlive.com

Vassar, Michigan–July 9, 2014 photo credit: Neil Barris, Mlive.com

But to fill the labor gap in their sweatshops, Chicago garment manufacturers began recruiting Mexican workers—the legislated quotas did not apply to Latin America—and St. Francis of Assisi quickly became an entirely Spanish-speaking congregation. All five of the masses today are still in Spanish.

As is any American who is not a member of one of the First Nations, I am descended from immigrants. One branch of my family immigrated in the colonial era. French Huguenots, they fled religious persecution, moving from one country to the next—the Dutch Republic, then England—not fully welcome anywhere until they came to rest among the Quakers in Pennsylvania, a place that embraced the outsider, the refugee, the stranger.

My many-greats grandfather, William Laux, was a wagonmaster in George Washington’s Continental Army. Family legend is that my ancestor’s wagon once got stuck in deep mud, and General Washington, mounted on his war horse nearby, waved an arm and shouted, “Go through, Laux! Go through!” I love this story. It’s so completely boring that it must be true.

***

So here we all are on this summer day in the twenty-first century: a DAR-qualified white woman sitting at a folding table, eating a chile relleno made by a Mexican immigrant–her grandson operating the tortilla press, her granddaughter taking orders in rapid-fire English, translating back in even faster Spanish to the grandmother. To my left, three generations of an African American family are eating Sunday lunch together. To my right, a Muslim family is ordering their vegetarian tacos—the head-scarved mother saying, “I walked by and knew by the smell that this is authentic cooking. I grew up in Texas.”

I walk into the relative cool of the church nave. In gold lettering above the entrance is the invitation: “Let us come with confidence to the throne of grace, that we may obtain mercy.”

I light a candle and pray for hospitality. Give us courage to be good neighbors. I pray for the confidence in God’s abundance that drives out fear. There is enough for all of us. There has always been enough.

This is the America I want to live in.