Somewhere around the turn of the century, Andrew Vander Wagon, who was never an officially licensed pastor but became one anyway, determined to build a bridge across the Zuni River because he was tired of being on the outs. The brand new CRC mission in the Zuni pueblo stood just on the other side of the river, which often wasn’t a river, per se, but then again too often irritatingly was.

As long as the mission stood that far outside the pueblo (it’s at the heart of things today, by the way), he was determined that his mission of missions would be crippled. Furthermore, when water actually flowed in the Zuni River, his only means of getting across was up on the shoulders of a Zuni man whose grace was abundant but, according to Andrew, unnecessary.

He told the tribe that he’d like to build that bridge, but the tribe’s eyebrows narrowed. If the gods wanted a bridge over the Zuni River, they told him, there would be one. Andrew told them that was nonsense (no one knows how he phrased his reponses, but “nonsense” wouldn’t have been, at that time at least, far from possibility with him). He built the bridge, and it lasted almost 20 years before a bigger and stronger one was finally constructed.

Here’s Brother Andrew’s bridge.

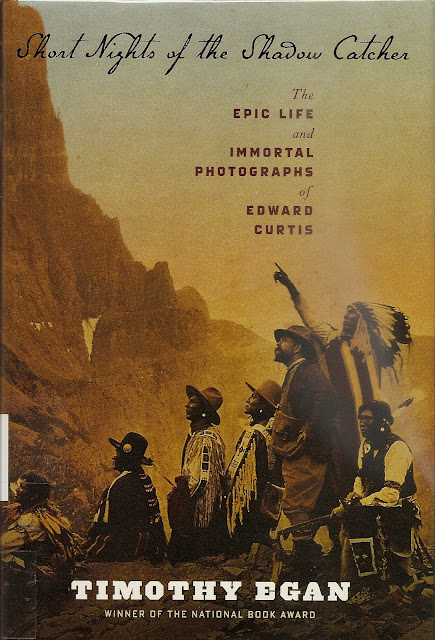

Timothy Egan’s fine biography of Edward Curtis, Short Nights of the Shadow Catcher, makes it abundantly clear that Curtis, the photographer, himself the son of a madcap missionary to Minnesota’s Ojibwe, was right there at Zuni pueblo during what might well be considered Andrew Vander Wagon’s reign as the mission king. I know enough about Vander Wagon (I share some of his DNA, by the way) to know that it’s impossible to think the two would not have met–Brother Andrew cut that kind of swath, believe me.

That meeting–at least in my imagination–must have been memorable, Curtis hating Christian missionaries (his father was preacher) as much as Brother Andrew loved being one, both of them immensely larger-than-life characters, the courses of their lives determined severely by a unflagging sense of their individual callings: Brother Andrew to alter the lives of the Zunis for eternity, Eastman to hold back the tide of white culture and document a way of life that was vanishing, in part because Brother Andrew was doing exactly what he was doing.

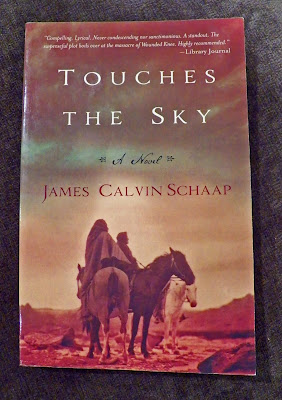

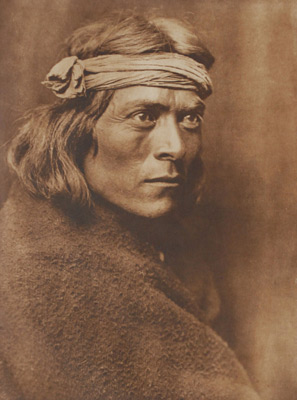

I didn’t know much about Curtis’s life, but I knew his work because I used a portrait of his on the cover of a novel of mine, Touches the Sky. Here it is.

In fact, it’s quite likely that everyone has, somewhere along the line, seen a Edward Curtis portrait. He made documenting Native America at the turn of the century his life’s mission. Nothing else mattered. His wife left him, and with good reason: he was no more her husband than Andrew Vander Wagon. His family despised him, save his children, who generally adored him.

Basically, he did all of that without pay, so he died unknown, penniless, an old and angry man.

But he’d once been a friend of luminaries, of President Teddy Roosevelt, who appointed him the official photographer for his daughter’s wedding. He gained the bucks it took for him to travel all over the west from J. P. Morgan, whose railroad empire was, as Egan deftly points out, doing as much as anything or anyone at that very moment to destroy the very cultures Curtis himself wanted to preserve with his portraits.

Neither Curtis nor Vander Wagon, despite their passionate callings, was above skullduggery. Both pushed envelopes. Curtis’s portraits often were deftly posed, even though he wanted his viewing public to see them as true-to-life candids. Some were anything but. Some of his “indian braves” were outfitted in regalia none of them wore by, say, 1915, which made Curtis little more than Buffalo Bill with an expensive camera.

Vander Wagon didn’t know how to color within the lines either. He was, more than once, fired. He was as good a trader with the Zuni and the Navajo as he was a missionary. When his colleagues disagreed with him and his wild ways, he went quite offensively on the offensive. He could be a dirty rotten stinker, and I may be unduly sweet to use such cute language.

But both absolutely loved their respective callings. Both were passionate about what they did. Both were given to sacrificing everything for what they felt called to do. They were, in some ways, partners in both crime and salvation.

As Egan points out in his fine biography, no one appreciates the work of Edward Curtis today more than Native people because his work–whether or not it was staged or posed–does exactly what he wanted it to do: it tells a story that ended when what some Native folks I know call the “illegal immigration” of white people to North America became a flood.

Fiction can go where history can’t, of course. And the mere idea of a meeting, on that bridge, between Brother Andrew and Edward Curtis, right there in Zuni pueblo, circa 1910 or so, beckons me to take a shot at the story. Curtis hated missionaries; Brother Andrew never met a man–white or Native–he didn’t try to strongarm to the Lord. But what linked them in an ironic way was a love for the people in that pueblo.

I don’t know if I’m a good enough writer to put that story on paper, but after reading Timothy Egan’s fine biography of the passionate life of Edward Curtis, I know I’d have loved to be there.

Edward Curtis, A Zuni Governor