Alexander B. Upshaw, the son of a Crow warrior of some renown among his people, was one of many young Native Americans sent off to Carlyle School, the flagship of Indian boarding schools, in Carlyle, Pennsylvania. He spent nine years there, and became a true believer in the philosophy of assimilation espoused by the school’s founder, Captain Richard Henry Pratt, who famously claimed that the most effective way of dealing with “the Indian problem” was education whose emphasis was to “kill the Indian and save the man.”

Clearly, Upshaw, upon his graduation, bought that philosophy. When he was photographed at a Chicago exhibition in what seemed like cowboy attire (not traditional Native dress), he wrote a rebuttal to rumors that he’d become, once more, a “blanket Indian,” and published it in his old school paper. “Alex,” he said of himself, “would have his schoolmates know that he is trying to be a man, although in the midst of trials and tribulations.”

When he left Carlyle, he went on to Bloomsburg College, perhaps the only Native kid to go there after an education at the famous nearby Indian boarding school. Here, he showed inclinations toward acceptance of evangelical Christianity, which would have been greatly accepted by white folks as an earmark of his assimilation into the majority white culture.

But assimilation after Carlyle wasn’t easy. Upshaw spent some significant time with Edward Curtis, photographing and researching American Plains Indians for Curtis’s monumental photographic and ethnographic project, The North American Indian. In his book, Short Nights of the Shadow Catcher, Timothy Egan says that Alex Upshaw’s work with his own people, as a kind of cultural mediator, had to have been difficult for him because what Curtis was doing was almost exactly what Carlyle had taught Upshaw to disdain–to remember and even take some glory in the old Native ways of his people.

Curtis used Upshaw as a translator, someone who could get beneath the subterfuge that would undoubtedly have been Curtis’s own misfortune had he not had Upshaw around to guide him.

What’s ironic and immensely sad is that Alexander B. Upshaw became, in essence, exactly what the Carlyle philosophy determined he should be–he was educated in the ways of the white people, he was industrious and ambitious, he was interested in history and culture and ethnology, he even married a white woman–although that was, to many, a step too far. Even though all of that was true, he suffered immense prejudice and personal problems.

Edward Curtis’s debt to Alexander B. Upshaw was significant, and Curtis makes that clear in his own acknowledgements. Without him, Curtis would not have determined that Custer’s death at Little Big Horn lacked the elements of heroism which white America attached to it when it happened in 1876. Upshaw translated the memories of Crow warriors who had acted as guides to the Seventh Calvary because of their own hatred of the Sioux and Cheyenne. Those elders made it clear that they believed Custer had watched American troops die in the attack on Captain Reno, his colleague, because Custer was interested in greater glory for himself, a critique which still haunts the story that rises from the open plains at the Little Big Horn.

Upshaw eventually became a critic of Washington’s continuing abandonment of the Native people they’d dispossessed. During those later years, he frequently drank too much, and eventually died in a stupor in a Montana jail. To this day, the Crow people claim he was beaten by those who thought they had reason to hate him, then dragged behind bars to die.

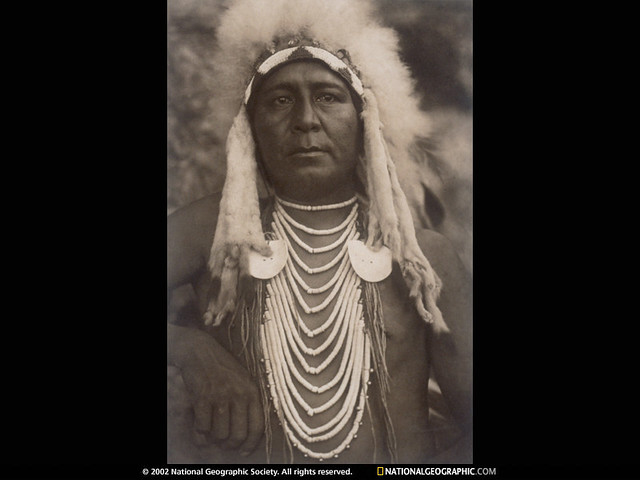

The portrait Curtis took of Alex Upshaw is itself mightily ambiguous. Upshaw didn’t have traditional long hair. He dressed in jeans and the kinds of buttoned shirts Curtis himself wore. At the turn of the 20th century, Alex Upshaw didn’t look “Indian.” Day to day, he looked like a good grad of Carlyle school.

Yet the portrait (above) has him in a war bonnet and authentic Native accouterments.

Was it Curtis who wanted him to look like his people traditionally looked? Or did Curtis just want something akin to a cigar store Indian? Or was it Upshaw himself, perhaps, who wanted to appear as if he were “a blanket Indian”? Does that famous photograph show him honestly or deceptively? And what did he think of posing as he did?

We’ll never know.

But this week we celebrated Columbus Day, a good time to remember the story of indigenous people in this country, a story some people have forgotten and more and more and more never hear or heard.

That’s a story told in the life of Alexander B. Upshaw.